"Argentina’s initial massive depreciation, as measured from the third quarter of 2001 to the second quarter of 2002, was 275 percent—as shown in figure 1. Then by mid 2003, the nominal exchange rate had bounced back somewhat to a depreciation of just 200 percent (from 3Q 2001) and has subsequently remained remarkably stable. Since 2002, the nominal exchange rate has remained at 3 pesos per U.S. dollar, ± 3 percent....If one presumed that the pre-crisis exchange rate in early 2001 was roughly at purchasing power parity, then a sustained 200 percent devaluation (the value of the dollar rises from 1 to 3 pesos) will eventually show up as a 200 percent increase in the domestic price level. Producer prices, which are more directly affected by the exchange rate, will react faster than consumer prices. And by early 2007, producer prices have already risen more than 180 percent while consumer prices rose by just 90 percent. Thus, at 3 pesos to the dollar, Argentina faces several more years of substantial inflation in its CPI before the fixed nominal exchange rate eventually ends it. "

"Korea followed a somewhat different monetary cum exchange rate policy. Following its great crisis of late of 1997-98. To be sure, Korea’s crisis was less intense than what Argentina experienced four years later — at least as measured by the initial depreciation, where the won per dollar rate rose “just” 85 percent (figure 3).... However, the big difference between the two countries in their post-crisis experiences is that Korea opted not to stabilize the nominal value of the won at a highly depreciated level, as Argentina did. Rather the Bank of Korea opted to let the won continue appreciating, albeit somewhat erratically, as shown in figure 3. "

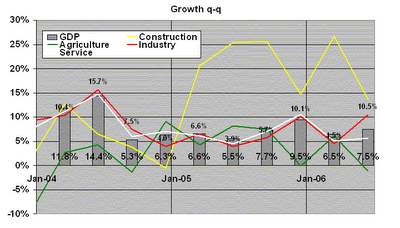

What about Turkey? To understand the rate of change in variables, the graph below is in log terms. "Energy" represents the cost of energy imports.